My Design Thinking Pattern

The Origin Story

In this post, I will describe how my own approach to design problem solving formed as a pattern (something I see as more flexible and fractally nested than a “process”), how I find it useful to approach the big problems that claim significant tracts of my own “mental space” like achieving climate justice and global sustainability, as well as what it looks like in action as illustrated by one of the core projects I executed at Sunrun, the largest American provider of residential solar power.

My problem solving approach stems from the need to “find a way in” to these wicked problems. With massive solution spaces and a minefield of unintended consequences, these problems are easily deemed “unsolvable” or “intractable”. But by mapping, breaking down, and zooming in to the many subsystems and actors in these globe-sized problems, I attempt to design and implement solutions that affect real change.

From a young age, I was shown the value of thinking about the state of the world differently than it exists today. Strange as it may sound, much of this came from a tri-generational organic farm and camp for children ages 7 through 12, a place called Journey’s End Farm Camp. Journey’s End changed my life by opening my mind and training me in kindness, cooperation, creativity, simplicity and environmental awareness. By connecting with my fellow campers and the farmland surrounding us, I developed an early concern for others and the protection of Earth’s natural splendor.

A typical scene at JEFC.

I still remember the feeling of shock and disappointment when I learned, sitting cross-legged in the rich soil of a fern-filled gully at the age of 9 or 10, about the distribution of food across the globe. The lesson began with a simple illustration--a basket of bread filled with enough for everyone in the circle to enjoy. As my fellow campers passed the basket, each helping themselves to what at first seemed an abundance of bread, the first to receive the basket took what I now recognize as the colonial share. By the time the basket had been passed to the far side of the circle, the remaining campers were left with crumbs. This alone felt like a serious injustice.

But when Carl Curtis, camp director, went on to explain how our global food system produced similar results for hundreds of millions of hungry people around the world, I was irrevocably changed. As they did twenty years ago, feelings blending indignation, shame, and a desire to make change still bubble up when I revisit the scene. I had to do something. But what?

Today, I answer that question with design thinking.

The Process in Action

This desire to make tangible improvements to the quality of life on Earth became a driving force in my life. It has also become a core goal of my design mind’s operation. I prioritize the solution of dire problems--the sort of problems captured in the Millennium Development Goals. Extracting profit from users’ monetized attention spans or manufactured desires just doesn’t scratch the itch.

The Conditions

What makes for an interesting problem?

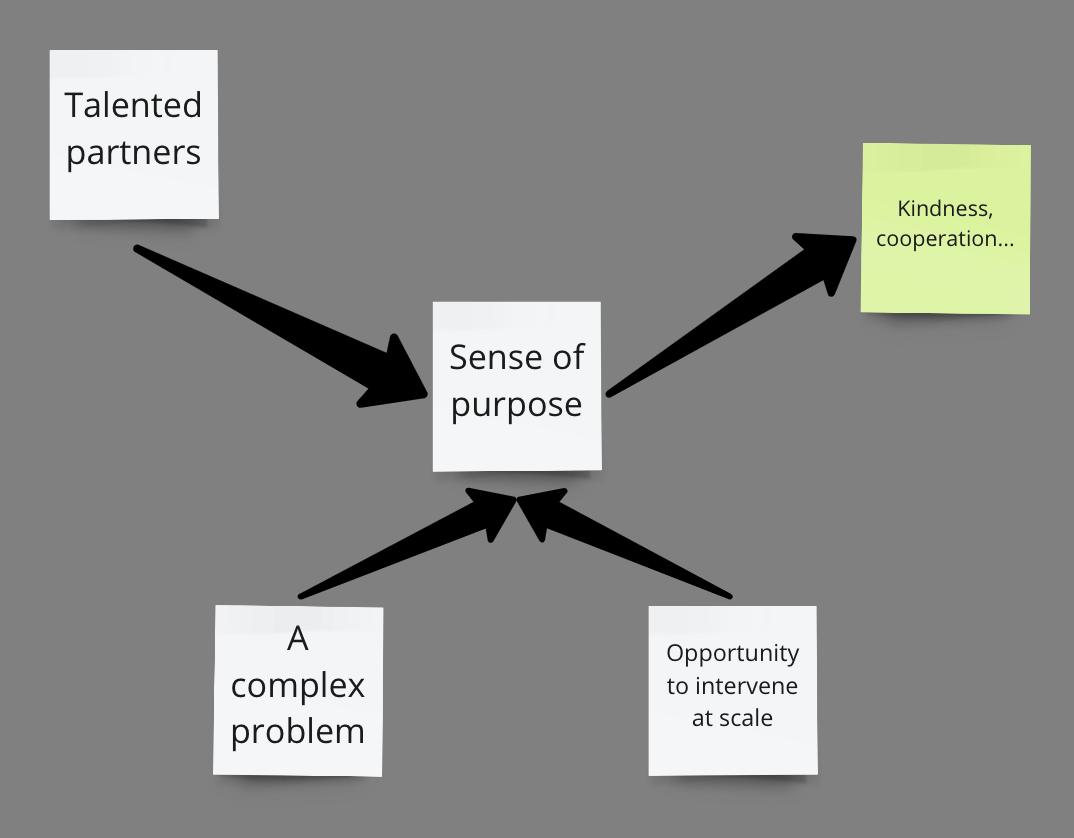

But when the right conditions are present, my thought process comes alive. First, the problem at hand must be complex, and ideally with opportunities for impact at scale. It must also connect to my sense of purpose. Finally, I like to add other talented partners with different mindsets and skillsets to broaden the spectrum of ideas we might realize together. When these factors combine, my values of kindness, cooperation, creativity, simplicity and environmental awareness can flourish.

These very conditions came together in the years I spent focused on the adoption of residential solar power at Sunrun. Working there was an opportunity to deliver a vastly improved service (clean energy in the home) at a cost and environmental savings. A typical installed system might save a family $25,000 or more versus expected utility rates while eliminating 100+ metric tons of carbon emissions--a personal and planetary win.

Unsurprisingly, 90% of American families express support for the expansion of solar technologies. And Sunrun has grown to be the largest provider of residential photovoltaics in the United States; but just 2% of American households are powered by the sun.

This mismatch between support for solar and actual installations has fascinated me for years. At first, I tried to make a direct impact on solar adoption as a salesperson, and helped 100 families start that change. But as a member of the Customer Realization team, we instead focused on improving the journey of the customers who expressed that initial interest in switching, but ultimately withdrew from the process before their system was made operational. Asking, “what causes customers to reverse their decision?” spurred us to examine their journey from start to finish.

The Formative Phase

The Formative Phase

In which the problem is initially understood, empathized with, and situated among other similar problems.

Looking into the data revealed that the number of initially supportive customers was dramatically trailing the number of successful installations. The sunk costs associated with cancelled orders presented a major business challenge for Sunrun.

Although solar technology is actually quite simple, we empathized with the homeowners rife with skepticism and mistrust from the trying experiences they associate with both home improvement projects and their existing electrical service--usually provided by a utility built to prioritize return on investment over customer satisfaction. Something was leaving customers with cold feet, and we needed to understand what.

Studying the emotional journey that takes place between the moment customers sign a preliminary contract promising a custom system design and the “flip the switch” celebration at the end of construction and inspection, which can range from as fast as a week in California to agonizing years in Hawaii, it was evident that we weren’t delivering a smooth experience. We saw how moments of doubt and miscommunication caused fully half of initially committed customers to abandon their order.

Once again, I found myself looking for a way in.

The Analytical Phase

The Analytical Phase

The vacillation between research and contemplation that drives idea generation and innovation.

The diagram above shows the Analytical phase of my design thinking pattern. It’s where you’ll find me asking questions, listening to stories, doing comparative research and analysis hoping to make connections and find understanding of the problem at hand. I think of this phase as having a “research” pole that is balanced by a “contemplation” pole which thrives on discussion with partners, quiet hikes and cups of coffee, early visualizations, and the rumination and productive procrastination also crucial to good thinking. Vacillation between these poles fuels idea generation and innovation.

After conducting and synthesizing interviews, reconstructing what went wrong on problematic jobs based on internal notes, and mining the experience from more than 1,000 sales calls in my previous role, we concluded that the breakdown of trust through poor communication was a tipping point for customers who ultimately cancelled their order. I needed a creative way to disrupt this costly pattern.

The Creative Phase

The Creative Phase

Where prototyping and iteration produce successively better solutions to the problem at hand.

Often, a lack of trust meant that embarrassing or deceptively simple questions weren’t being asked. Working from the hypothesis that these unasked and unanswered questions were causing buyer’s remorse, I set out to prototype an intervention that could preemptively address these concerns.

First to emerge was a Q&A addressing the most common misconceptions that later grew into misunderstandings and cancellations. Next, we imagined how we might ask these questions of all new customers. Serendipitously, I had been around long enough to remember an older process that had been abandoned, but might be reborn for our new purpose. We prototyped a reimagined welcome phone call that would confirm crucial details and revisit concepts key to a successful installation journey.

I made the first few calls manually, roughly jumping between a Google Doc and Form to capture customers’ responses. As early issues were uncovered and resolved, a trend emerged: customers who completed the call were advancing to subsequent process milestones at higher rates.

Feedback in hand, we cycled back, further cutting and polishing the facets of our emerging gemstone, striving for a simple yet effective solution. Next, we connected the data capture and script generation to Salesforce, enabling us to ask relevant questions of customers with troublesome utility providers, local complexities, or more complicated installations.

With each iteration, we captured the feedback of customers, salespeople, call center workers, and project managers, all of whom could now see the results of this call and tailor their responses with customers accordingly. This feedback fueled the refinement of the solution and creation of new features, like capturing a score for the confidence with which customers responded, allowing us to identify customers who might need more hands-on attention.

This working prototype was rolled out first to the inside sales team, then field sales, and progressively made required in all states for orders to progress through the operations process.

In Conclusion

The numbers complete the story.

Those who completed a call were over 10% more likely to reach a successful installation.

In 2019, over 95% of Sunrun’s new customers completed this call. At that rate, nearly 100,000 new customers will complete the call in 2020. Through this deceptively simple intervention, we improved the communication and journey for thousands of customers who might otherwise have joined the cohort of frustrated and confused former customers. This small elimination of frustration and friction allowed more people to adopt renewable energy.

I relished the feeling that each avoided cancellation was both a personal and business victory. Expanding my leverage beyond individual customers, design thinking allowed me to scale up to changing systems that affect nearly every new customer at the biggest solar company in the country. Now that’s a platform to address the adoption of clean energy.

I hope that this illustrated example allows you to see the reality of one designer’s pattern of problem solving. I feel great fortune that this way of thinking has given me the opportunity to do work I love while making a positive impact.

And from the looks of it, there are plenty more problems ahead for a lifetime of challenging, but satisfying design thinking.